WTF is ASGI and WSGI in python apps?

I’ve been working on Python-based backend development for about three years now in various forms. I primarily use Django and FastAPI, although I initially started with Flask. However, during my backend work, I frequently encountered the terms ASGI and WSGI. For example, one of my Django deployment scripts included references to asgi_app and wsgi_app, and used gunicorn to deploy these apps. Although I initially dismissed these terms as implementation details, I now find myself needing to support both ASGI and WSGI apps for my company tensorfuse. As a result, I believe it’s important to explain ASGI and WSGI to a wider audience.

Life cycle of a request?

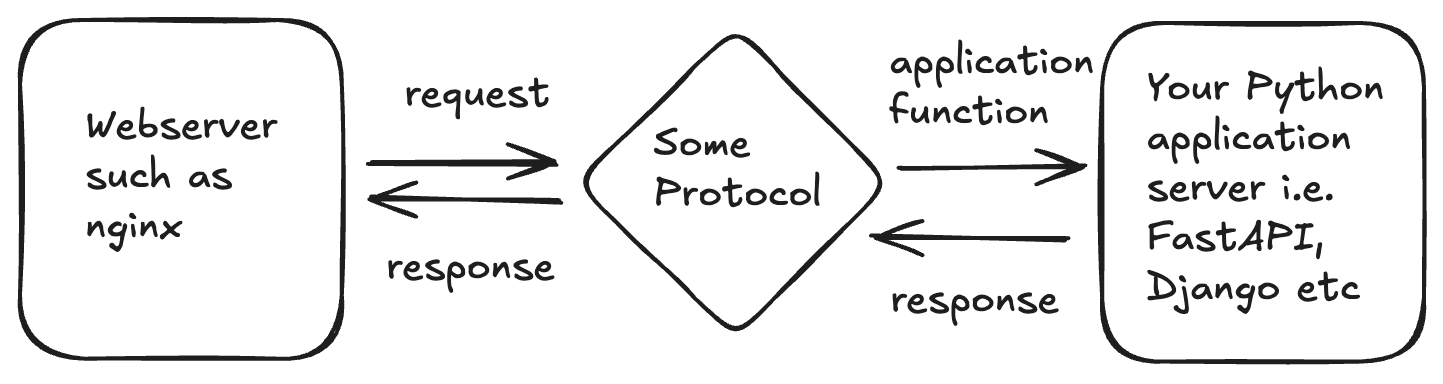

When a client sends a request to a server and gets a response, a few things happen behind the scenes. First, a process on the server keeps an eye out for incoming requests on a specific port. When a request comes in, the process checks the protocol and what needs to be done to handle the request, like decrypting a secure connection. Once the parsing happens, the request is routed to a path where your application logic sees the request, carries out the appropriate action and prepares a response. Finally, the response is sent back to the client through the server’s ports.

Throughout the entire lifecycle, certain processes will always occur when handling requests, such as listening on a port and SSL termination. These processes are not related to the business logic of your app and are likely to be similar across most apps. As a result, app developers should not be concerned with these common plumbing scenarios. Instead, they should focus solely on the processes that are unique to their business logic. In other words, they should only be responsible for the part where the application logic handles the request, prepares the response, and leaves everything else to be managed by something else.

Web server vs web framework vs a gateway interface

This is where the distinction between a web server and a web framework comes in. Web frameworks, such as Django, FastAPI, and Flask, allow you to focus solely on the application-specific code. With these frameworks, you can specify the routes and write the business logic for each specific route without having to worry about the details of how requests are received, streamed, decrypted, or how responses are streamed. This means you can focus on what will happen when a request comes to a specific route. Other common details, such as request streaming and SSL termination, are taken care of by a web server, examples of which include Gunicorn, Uvicorn, and Nginx.

What is a gateway interface?

There are a ton of web servers -> Gunicorn, uvicorn, nginx, etc, and a ton of Python web frameworks -> Django, Flask, FastAPI, etc. Maintainers of these projects will have to design m * n combinations of interactions which would be super tedious for both. This is where the need for a gateway interface comes in. A gateway interface defines a common protocol (a set of functionalities) that each side ( the server and the framework) needs to implement. Once they implement this interface they instantly become compatible with each other. So instead of worrying about m different servers or n different frameworks, each server and framework needs to implement the gateway interface. There are two popular Python gateway interfaces - ASGI (Async Server Gateway Interface) and WSGI (Web Service Gateway Interface).

The Async Server Gateway Interface

The ASGI interface is the latest Python gateway interface that supports asynchronous handling of requests. It is a living document that specifies how the web server will communicate with the web framework and how the web framework will communicate with the web server. ASGI is a very simple interface to understand and it essentially consists of a single asynchronous callable that needs to be implemented by the web framework. This async callable takes a scope, which is a dict containing details about the specific connection, send, an asynchronous callable, that lets the application send event messages to the client, and receive, an asynchronous callable which lets the application receive event messages from the client.

async def application(scope, receive, send):

event = await receive()

...

await send({"type": "websocket.send", ...})

The ... part is handled by the web framework, and it’s the responsibility of the web server to call this async function by setting up the scope, receive, and send parameters. When a request is received by your server, it creates a scope dictionary to identify the connection and then sets up receive and send functions that allow the application to send and receive events. All the information about the request and response is transferred between the web server and the web socket using these receive and send functions. An example of an event that your web framework might receive when calling event = await receive() with the body from a HTTP request:

{

"type": "http.request",

"body": b"Hello World",

"more_body": False,

}

The web server prepared this event for your framework to consume and now it is the responsibility of your framework to prepare a response event and use send to send back the response to the web server which will then forward it to the client. And since all of this is created using async/await your main thread is not blocked by I/O while using ASGI compatible frameworks and servers and hence you can serve multiple requests at once.

The Web Service Gateway Interface (WSGI)

The main difference between ASGI and WSGI is that WSGI is not asynchronous, which means it blocks the main thread when it receives a request, making it slow and unable to handle multiple requests simultaneously. On the other hand, ASGI is more advanced and better suited for newer projects. Let’s take a closer look at the WSGI interface, which is a synchronous function that takes two positional arguments: environ, containing all the details of the incoming request, and start_response, which accepts the HTTP status and headers as arguments. This function returns the response body as an iterable.

def application (environ, start_response):

# Build the response body possibly

# using the supplied environ dictionary

response_body = 'Request method: %s' % environ['REQUEST_METHOD']

# HTTP response code and message

status = '200 OK'

# HTTP headers expected by the client

# They must be wrapped as a list of tupled pairs:

# [(Header name, Header value)].

response_headers = [

('Content-Type', 'text/plain'),

('Content-Length', str(len(response_body)))

]

# Send them to the server using the supplied function

start_response(status, response_headers)

# Return the response body. Notice it is wrapped

# in a list although it could be any iterable.

return [response_body]

Echo server in ASGI and WSGI

Now let’s build an echo server in ASGI and WSGI to get a practical feel for the gateway interfaces.

async def app(scope, receive, send):

if scope['type'] == 'http':

# Send the response headers

await send({

'type': 'http.response.start',

'status': 200,

'headers': [

[b'content-type', b'text/plain'],

],

})

# Process the request body and send response in chunks

more_body = True

while more_body:

message = await receive()

body = message.get('body', b'')

more_body = message.get('more_body', False)

# Send each chunk of the body immediately

await send({

'type': 'http.response.body',

'body': body,

'more_body': more_body

})

Let’s break down this ASGI server -

- We start by sending the response headers with a 200 status code and ‘text/plain’ content type as soon as the application is called. We just verify if the request is an http request.

- Instead of accumulating the entire request body, we process it in a loop:

- We receive each chunk of the request body using await receive().

- We extract the body content and the ‘more_body’ flag from the received message.

- Immediately after receiving each chunk, we send it back as part of the response:

- We use the http.response.body message type.

- We set the body to the chunk we just received.

- We set more_body to True if there’s more data coming, or False for the last chunk.

Now let’s build a similar echo wsgi server.

def application(environ, start_response):

status = '200 OK'

headers = [('Content-type', 'text/plain; charset=utf-8')]

start_response(status, headers)

# Read the request body

try:

request_body_size = int(environ.get('CONTENT_LENGTH', 0))

except ValueError:

request_body_size = 0

request_body = environ['wsgi.input'].read(request_body_size)

# Echo back the request body

return [request_body]

- We first return a

200 OKresponse to the server. - We then get the content length fron the

environdictionary and use it to read request body - We then return the request_body as an iterable (

listin this case) - For large request bodies you can also use a generator